Clicking and clacking, the drumsticks announce swerves, dips, bumps, and turns in the road. Now and then I look down at the gift for my brother. My adolescence would have been an excruciating feat without him, while his own tumultuous childhood was only made tolerable by the sticks perpetually glued to nerve wracked hands. In the seat of my car, they roll back-n-forth and rattle out memorable tunes of our desperation; the crescendo ceasing as my mind recedes into a crepuscular tempo, marking the past. I drive along, thinking of my lost brother and other trips we once made together along this road.

Some people throw stones. My brother did his best to shield me from the rocks and those who launched them in my direction. Try as I might, I could not protect him from the malignant affairs of life.

Saturdays, on those afternoons where bare feet are endangered by molten blacktop, Billy Jack would grab my hand on the walks to the swimming pool. Any time he and I were together in public he tightly held my hand, or else hovered. My face never failed to burn with embarrassment. He rarely sympathized or responded to the putty resentment, except when teasing.

“What’s the matter Kris, don’t wanna be seen holdin’ big brother’s hand.”

“You know dang well I don’t like it–and why.”

“Hey, I’m not protecting you from them, I’m protecting them from you.” He grinned, and pulled at my arm–me, swinging a size four tennis shoe at some sort of kickable refuse.

“Don’t ever forget, just ‘cause I’m a girl don’t mean I cain’t strike you out or take care of myself when hateful boys throw stuff.”

At church camp, in summer of ‘82, back when boys and girls could camp together, BJ caught a dinner plate size rock with the back of his head. The camp counselor asked the chucker, “Why did you do it, son.” The kid sniffled and stammered, “He was picking on me and I was scared because he’s a giant.” The counselor paced and worried, speaking to the picture of the Lord’s Supper hanging on a far wall, “But it’s such a big rock–the kid is going to need stitches and he’s most likely concussed.” Reaching over a What Would Jesus Do plaque on the desk, he picked up the phone and while dialing, shot a glance at my hunched over big brother then shook his head. “You’re as big as a man.” To the sputtering boy he said “I guess he bullied the wrong person, didn’t he.” I started to speak but the counselor held up a hand to “Shush” me as he spoke into the mouthpiece. “No ma’am, the church will not be responsible for a hospital bill.” Across the office, sitting on a couch and holding a towel to BJ’s bleeding head, I heard momma’s screeching from the phone. She sounded more animal than human. The counselor interrupted her rant. “No, Ms. McGee, your son is a delinquent and, as such, our church cannot be held responsible.” For a moment murmuring logic seemed to flow from mother’s end, but she was interrupted again. “We will not take him to the hospital–you must pick him up immediately.” The man pulled the device away from his ear as if it were alive. What he held in his hand hummed like the honey bee box I’d hit with a stick. Mom spewed disgust all over the camp counselor, the church, and her troublesome son. The call ended with, “Oh, you will also pick up your daughter. She attacked the boy your son was bullying.”

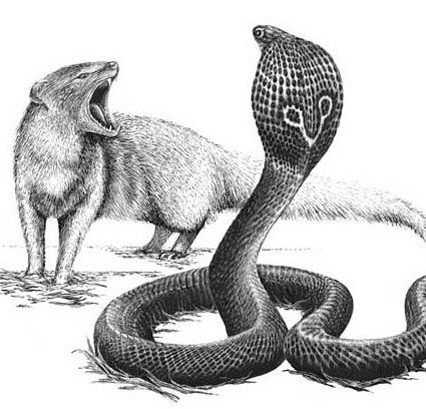

Truth be told, the boy tried to lure me into the woods, and because I wouldn’t go, he berated me. “Nobody wants your kind around anyway.” He pushed me to the ground. “WHY DON’T YOU GO TO AFRICA WHERE YOU BELONG.” Billy Jack heard the yelling and came running, only to meet the thrown rock.

Momma didn’t want to hear the truth anymore than the counselor did. After arriving home from the emergency room, she added a few matching knots to BJ’s sore head, then took away his most prized possession for a month. Mother always keyed in on her son’s beloved drum-set whenever she really wanted to punish. But she never kept it for long because he’d drive us crazy beatin’ on everything in the house until he got it back.

“Hey sis, guess what I dreamed last night,” he asked while we were watching cartoons.

“What, that in the alter-world mother actually is the ‘Wicked Witch of the West,” I popped off.

“Yeah, dummy,” he said while tapping a beat on the coffee table, then continued “It was Oz and you were a clueless brown Dorothy skipping down the yella brick road.” Pushing him and interrupting the rhythm, I spat. “Shut up, don’t say that.”

“Calm down, you started it.” Tat-t-t-tatat. “Anyway, I dreamed Charlie Conner came into our room while I was getting my groove on and said ‘Boy, you won’t find the beat until you’re lost in it.’”

“Stop all that racket will ya.” Mom’s voice was barely heard over our sibling discourse and the pitter-patter. BJ’s wide eyes cautioned me of the danger. He set the sticks down.

“That’s the dumbest dream ever.” I mumbled around a mouthful of Fruity-O’s, then inquired, “Who the heck is Charlie Conner.” BJ slapped a palm to his forehead, sighed and picked up the drumsticks. The unrelenting musical messages his head sent to his hands were hard on the tools of the trade. The sticks never outlasted their logos. After examining the Ludwig Stamps, both worn like battle scarred war paint, he said, “Charlie Conner.” Ding-da ding-tat-tat-tattattat! “He’s the inventor of the rock-n-roll eight count beat.”

“SHUT UP”, came from the kitchen.

“Ohhh, that Charlie Conner. I thought you were talkin’ bout the guy T-Bone brought over who drank all momma’s wine and got sick all over the couch.” I paused before adding, “Billy Jack, that’s ridiculous. How can a person get lost in a sound, anyway?”

“Would you quit comparing a living legend to a drunken mutt. He’s Little Richard’s drummer.” Sticking me in the arm he continued “If not for him, there’d have never been a Bonham or Ward or any other decent skin beater.” I looked at him with cross-eyed questioning. Exasperated, he said, “John Bonham. Bill Ward. The rhythm keepers of Zeppelin and Sabbath,” and bounced the sticks off of an empty cereal box.

“I said HUSH.”

Now wedded to another world, with a look akin to something you would see in the eyes of a zealous church congregant belting out Amazing Grace, my brother continued his roll. Having not much in common with the hymns of old, his playing was as beautiful and, surely, just as pleasing to God.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” mom raged as the curly cue cord began to unravel from the wall phone. “I’m talking to my boss. Stop all of that noise or I’ll…” Overruled by a fully extended phone cord and over-matched by the spectacular living room solo, mother’s wrath would not penetrate Billy Jack’s splendor. Now only a few feet away, with greenish slits glaring, her blond bangs bounced in time to the end of the fly swatter, shaking a promise at us. BJ’s own golden locks hung between bare knees, almost touching the combat boots his feet had yet to fit into. Lids now tightly shut, there’s no telling where his cornflower blues had gone. They were eyeing something in the darkness, though. Something more glorious than the world around him. Something no one else but my brother could see. I whispered, “I wish you could come back and mom would get lost in a beat.”

Don’t know which she hated more, his constant drumming or Billy Jack himself. Nothing was safe from his unexpected eruptions, nor was he ever safe from mom, unless T-Bone was around. Whenever BJ wasn’t in our bedroom playing his own set–an overturned laundry or fruit basket might become a snare drum, the table would do as a tom-tom and stomping the floor stood in for a base. If mom couldn’t access a belt–a hairbrush, flyswatter handle, or ring-studded backhand would suffice in response to his usually innocent misdeeds. She hit him, he hit the drums: a steadfast competition between who or what must suffer the most.

My brother’s musical talent seemed like a birthright. Mother’s mistreatment appeared to be its twin. To say he suffered abuse is an understatement. Not sure who slapped him first, the OB-GYN or mom. I don’t believe she tended toward violence before having BJ, and the jury is still out on justification. Him being her first born offered the first chance to hit on a kid and not be held accountable. Also, beatings she withstood from his father only stopped while carrying BJ. Fortunately Vietnam’s draft preserved her and the unborn child. At least that unpopular conflict became someone’s salvation.

After coming home, his daddy, full of Quaalude and Johnnie Walker, stood on the railroad tracks behind our house with arms spread like he was waiting for a hug. A southbound Kansas City Southern and eighty coal cars willingly obliged. Mother always said, “His spirit made its last stand in ‘68 at Khe Sanh and life just was not worth living after that bloodletting.”

She whipped him because he looked too much like his father. She whipped him because he sounded too much like his father. She whipped him for my indiscretions and she could even figure out a way to blame him for her own misdeeds, then whip him for vindication. He constantly stayed bruised for being born left handed. Apparently, his father had been a lefty. The assaults were never ending, but Billy Jack couldn’t seem to get enough because he also caused a lot of trouble which called for more ass-whoop-pings. The punishments always outweighed his conduct, whereas misbehavior on my part rarely drew much fire from anyone.

BJ never knew his dad and my own was a mystery to me. Mother wasn’t promiscuous, just hard to live with. Until T-Bone, I don’t remember her dating anyone. Except when mom would kick him out for some reason or another, (like when he sold the Airbag idea to the “suit wearin’ foreign guy” for $250 and beer for a year; a contract on a barroom napkin), he was around throughout my adolescent and teen years. I loved the old grease monkey, and in his own way, I always felt he loved all of us. Even when I meticulously painted, with ‘Passionate Pink’ nail polish, every other spoke on the front of his Harley, the most I got from him was a little hurtful teasin’.

“Girl, I’d tell your daddy on you if we knew who he was,” he said while rubbing the spokes with momma’s nail polish remover and complaining ‘bout his cracking knees. “I’ll bet he’s one of those looney’s out atcha mom’s workplace. Just wait till I find him,” he kept pickin’ as I giggled at the folded over funny looking father figure. With the pointy little welders cap, the dirt and grease burnishing his hands, face, and everywhere else the tank top failed to cover, he resembled the Tin Man. I always felt like oiling his bad knees.

Mather’s workplace was the ‘Deep Woods Tranquility Home,’ located a few miles outside of our tiny Northeast Texas town. It was there, at a Christmas party, I first noticed the beginnings of Billy Jack’s dark side. I didn’t like going to the hospital because mom was such a big ol’ fake in front of her co-workers and patients; like she should get a ‘Parent of The Year’ award or something. Plus, I’d taken T-Bone seriously and spent most of the time sizing everyone up for paternity.

After passing the guard shack, I stared out the back window of our Chrysler and wondered for the millionth time if Mr. Sims was my father. As we drove toward the main parking area, I twisted the dark coppery orange curl uncoiling from under my beanie while scrutinizing the charcoal sideburns springing from the sides of his uniform cap. His skin shined a deep ebony and mine matched the ‘Piggly Wiggly’ grocery sacks kept under our kitchen sink. No, I didn’t resemble Mr. Sims, too much, nor anyone else in our small town. Hell, I was even a novelty in a family of oddities–a caramel complexion separating from those I loved. White and black makes brown and brown doesn’t mix with white any more than black does. I seemed to notice it more than they did, though.

A mansion, originally built in the 1840s, and modified in the mid twentieth century, served as the administration office. The interior, gutted of all memories of the slave master who’d built it, now transformed into work cubicles and doctor’s offices, could not hide the remaining shell and what it stood for. From the outside, the colonial resistance continued on, supported by eight, twenty foot, rigid, marbled, albescent, columns. A scarlet brocade bunting smiled between the two center columns; its raised white letters spelling a paradoxical “Welcome” glared above an excessively large porch. The wooden surface, polished to perfection reflected its knotty pine brothers surrounding the house. As a child I looked upon this gigantic marvel in awe and wonder. In school, the bun-haired, mealymouthed teacher, taught that only a few decades prior, a person such as I wouldn’t have been welcome on that porch, unless she was pouring sweet tea or mixing mint juleps for those she served. As a teen and young woman, the smiling bunting became a vulgar and unwelcoming gash. Anytime I walked under it to enter the office, I understood that crossing the threshold cast a shadow which, in the not so distant past, would have never darkened that front door. But now, as a psychiatric hospital, the place protected no one from their unrealistic fears–and only trapped one in the drug induced safety of an unrealistic reality.

A long, broad driveway, once trampled upon by horses, and eventually traced by America’s first automobiles, no longer permits anything but foot traffic and the occasional ambulance. From the pedestrian gate to the administration office, six, five story buildings, built by the facilities originator, lined the way. With no windows, the sienna bricked monoliths squatted, three on each side of the way, facing each other in faceless showdowns. Without the waxy green ivy weaving its way up the walls and choking out the rain gutters, the buildings would look like run of the mill government housing projects in any large city. Together, the office and these structures mimicked antebellum and contemporary slavery in co-operation.

Daylight dwindles early in tree covered east Texas, especially in winter. Flinty shards and earth toned pea gravel lead up to and around a grand fountain before circling around to the first of sixteen steps. A ceiling of hard gray sky matched the flintstones crunching under our feet. The ivy and lichen covered bricks of insanity’s edifice towered over BJ and me as we walked in silence under the shadows of trees and treatment dwellings. He’s gotten quieter and quieter over the past couple months and I did not like leaving him alone in whatever universe he was stuck in.

“Who do you think’ll win the Super Bowl this year?” I asked, peering up into his downcast face.

“Hunh?”

“You heard me Billy Jack.”

“Yeah I heard you sis but I think you’re just talkin’ to talk,” he said in a hollow voice.

“No, I’m serious. I know it’s early in the playoffs, but who do you…”

With a storm in his eyes, he shot those cornflower blues toward me, gritted his teeth and said, “You don’t even watch football. You’re all about baseball. It’s always Rangers this, or Astros that, or the Yankees are bil ol’ cheats, or, or…” The tempest quickly subsided and his jaw relaxed before continuing, “Kris, you don’t have to act like there’s always something wrong. Why do you want to fix everything anyways.” Before the denial could fly out of my mouth, a scene caught my eye. Pointing, I said “Look it’s the sisters.” Intrigued, we stopped and watched while disagreeing, twin septuagenarians completely relieved a sticky holly bush of its leaves. One leaf at a time, they plucked and chanted in unison, “He loves me–he loves me not. He loves me– he loves me not.”

The Tschesky sisters were residents of ‘Deep Woods’ long before mother went to work there. This ritual was more than a lover’s question to the gods of fate, it was an annual competition. Every winter when the holly’s were covered in bright red berries and the leaves were at their sharpest, the twins would choose a lone bush and pull all but the last bits of foliage from it, one leaf at a time. Legend has it, one of the twins had a short affair with Lee Harvey Oswald and hides a secret the other sister and the rest of the world would like to know. But in order to learn the answer to that mystery, another enigma must be resolved. Which Tschesky was it? I guess, once the sisters settle on which one of them spent time with Mr. Oswald, the other puzzle must be solved.

Another year without a resolution passes as the twins abandon the last two leaves. The unresolved whodunit ending with a long hug and elderly shoulder-pats. Our mouths hung open as we watched them walk harmoniously toward the Santa Clause line–bloody handprints on each other’s backs. Picking up where we left off, BJ asked, “Why don’t you fix them, huh Kris.” He paused and continued, “Some people just can’t be mended. Yeah, you can patch ‘em up a little by smiling and saying nice things, or by trying to pull away from whatever they’re lost in with meaningless words…” Now waiving his arms at the buildings, the moment found its summit “… or you can even try to treat ‘em in places like these.”

Looking down at his father’s old combat boots he’d stuffed with paper and extra socks, he lightly kicked a pebble and spoke as if in a trance. “Nobody could fix our dad’s. Mine jumped in front of that train before I was old enough to help him. Yours, I remember. He was a nice guy but he chose his family over our momma. They just wouldn’t accept a white woman, her white son, and the little half-breed Kris to come.”

“Shut up Billy Jack.”

“No, you listen to me, little sister. What about mom, huh. Why can’t she be fixed? Why does she hate me so much? I never done nothing to be whipped all the time. Some people cain’t be fixed. You and T-Bone try to protect me from her but that’s just temporary and doesn’t work half the time anyway. All them kids that throw rocks at us and call you racist names can’t be fixed. Yeah, they can be controlled sometimes, or stopped from chucking things and their words, but that doesn’t fix ‘em. You cain’t make a bad person good no more than you can make a good person bad. Mean people and the patients here are a lot alike–it’s just a different kind of sickness.” His last words chasing a teardrop down his cheek, “Some people are just broke on the inside and only an inside job will fix them.” Our hands met in the cold space between us and we walked in quiet solitude, my mind awash in these new complications, and his reverting back into the hidden chamber he’s been crawling into lately.

The fountain and the makeshift Gingerbread house the hospital had put together, for patient and visitor Polaroids with Santa, came into view. A centerpiece of the old plantation, the fountain continued to be the focal point of the mental institution. Peeing Cherubs kept their business to themselves during the winter months. The huge bowl, absent its supply of water, served as a gathering place for pine needles and cones, and bits of rubbish representing humankind’s dependence upon chewing gum and vending machines. The line to Santa’s lap seemed to snake until after the New Year, so we made our way to the other side of the fountain to find a place to sit.

Standing on the bench we had in mind was a boy smaller than me, but his demeanor did not match his size. Because we’d never seen him in our past excursions to mom’s place, BJ and I figured he was a visitor here for the Christmas party. We quickly learned differently. With optimism contrasting the gray sky, he smiled into the distance, and began to play an invisible violin while absorbing the attention of an audience seated within his blemished mind.

“Come on sis, let’s throw rocks at ‘em,” Billy Jack said as he stooped and scooped up a handful of gravel before running the rest of the way around the fountain. Frozen. Appalled. My feet suddenly grew roots as I witnessed the caring and kind brother I’d always known and cherished turn into an intolerant and mean stranger while chucking small stones at the mentally ill child. I learned the meaning of stoicism as the little boy, with a newly brooklyn tooth and small cut on the bridge of his nose stopped his imaginary baroque symphony long enough to straighten his onyx arrow-headed bolo tie and starched cuffs before continuing the drawn-out push-n-pull of the unseen bow.

Was my brother’s newly acquired barbaric behavior an angry outcry at the injustice he’d been harping on–a response to our mothers savage and unfair treatment? Was it lying deep within a physiological plane, seeded in D.N.A., and sprouting as a result of life’s rainfalls? I don’t know if the egg came before or after the chicken. Our mother and BJ’s father were both broken people. That day, I stood planted to the ground of a place of nightmarish reality, watching a horrible boy, more like his mother, or his father I’d heard stories about, rather than the Billy Jack I’d always known. The Christmas season bringing a not so lovely gift–a thoughtless and mean stranger hatching before my eyes.

The last summer of sanity for BJ is memorable, mostly because the city swimming pool was out of commission. For the few weeks before we broke for those rapturous three months every kid dreams of during math and science classes, he was mostly himself. Except for moments when the private place beckoned his attention, he was the same ‘ol big brother who teased me one minute then protected me from the same kind of pestering, doled out by others, the next.

That summer, swimming in the public pool was out of the question. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal” had touched our town not long after his shortened last term. The federal monkey trickled down to our tadpole of a town and kissed it with the jewel three generations had adored. Every May through September since 1946, that aquamarine rectangle served our community with endless days of waterborne anesthesia. An escape from the heat and humidity of the south could only be found in two places: a commercial refrigerator or the Rondale city pool.

Well into its third decade, the north side of the deep end gave way to the roots of an oak tree that had staked its subterranean claim long before our bastion of coolness attempted a hostile landocracy. FDR’s plan did not include perpetual maintenance and the city budget was not braced to take on the task that year, so BJ and I were left up to our own devices. I dug both cleated shoes into a pitcher’s mound and became the first girl to pitch a six inning no hitter in East texas little league. Billy Jack did not fare so well. A mind numbing infernal pit of inhalant intoxication wrapped its insidious roots around his damaged and fluctuating emotional condition. The thin wall gave way to the eternal stateroom he’d faded in and out of for the last couple of years. The swimming pool would recover, but my beloved brother could not be rebuilt. With gold lips and teeth, Billy Jack spent most of that summer on the front porch perched on the same couch T-Bone’s friend had puked on, a can of spray paint in one hand and the other tightly gripping his drumsticks. These are the last recollections of my brother being at home.

Driving along the solitary route to the ‘Deep Woods Tranquility Home,’ the telephone wires rise and fall in steadfast compliance of the tar scented poles they are connected to. The blacktop, abutting high-wires, and drumsticks in the seat, respond to the waxing and waning of the landscapes’ ever changing expression. The road unfolds itself toward the next distant point of view, the wires carrying heavy loads of humanity’s binding conversations. From zenith to nadir-apex to antapex– hill to dale, roads, and words carry us through life. They are all influenced and escorted by the landscape or another. We are directed by whatever we are attached to. The loads we bear are held upon the shoulders of others. They not only carry burdens, but also the load-bearers. In fact, those who carry those, who carry loads, have their own loads to bear. Some people carry the loads, and still others transfer theirs, one chucked stone at a time.

Mom’s heart gave out after just fifty years of yielding to anger and resentment. T-Bones whiskey soaked liver made it almost to seventy before his Tin-Man knees took their last creaking step on a burnt out bricked road. BJ’s been a patient at ‘Deep Woods’ for the better part of two decades. I don’t know what is directing his thoughts and actions, but I still hold out hope he’ll be returned to the boy who protected me from rock throwers. Maybe his dream about ol’ Charlie Conner will prove true. Clicking and clacking, the drumsticks announced the swerves, dips, bumps, and turns in the road. Now and then I look down at the gift for my brother. Maybe he’ll discover his beat and get lost in it rather than continuing to hide from the unrelenting reality he could never really depend upon.

Ross Hartwell 1893452

Memorial Unit

59 Darrington Road

Rosharon, TX 77583